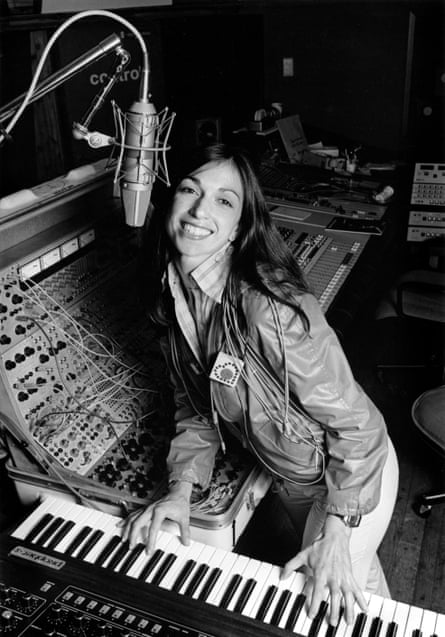

It might not seem so much of a stretch any more, but imagine spending your entire life in a tempestuous relationship with a machine. Not a sleek smartphone or tablet – we’ve seen how that can escalate in Spike Jonze’s Her. Instead picture a tapestry of tangled multicoloured wires, knobs and buttons, a bulky modular synthesizer otherwise known as the Buchla. Suzanne Ciani has spent much of her career testing the limits of one of these cumbersome instruments. So dedicated to its oscillating drones, burbles and bleeps did she become that has jokingly referred to the Buchla as “her boyfriend”. At times that affair was “traumatic”, she says now, down the phone from her studio in the Californian coastal enclave of Bolinas, sounding like both Marilyn Monroe and a Woodstock hippie. “Technology’s always very risky – you never know when it might break.”

Ciani is one of electronic music’s earliest but lesser known pioneers, dubbed variously as the “diva of the diode” and “‘America’s first female synth hero”. This weekend she’ll be one of the recipients of the Moog Innovation Award at Moogfest, the synth brand’s celebration of electronic music and technology, alongside Devo and Brian Eno. Ciani, however, has been quietly innovating in various fields of music and sound design for nearly half a century. She was one of the few women on the frontline of electronic innovation in the 1970s, a five-time Grammy-nominated recording artist, a pioneer of the new age genre and the first solo female composer to soundtrack a Hollywood film. Brilliantly, she also invented Coca-Cola’s infamous “pop and pour” sound effect.

Today, however, she has returned to the Buchla, an instrument that it seems will always have her heart. Ciani was introduced to it by the inventor himself, Don, while she was studying music composition at the University of California in 1970. As the sleevenotes for one of her compilations put it, the Buchla was “San Francisco’s neck-and-neck contender to New York’s Moog … run by a community of festival freaks and academic acid eaters.” Ciani soon established herself as a Buchla buff and moved to New York, when the Soho avant-garde circles were swirling at full tilt and she was living among musicians such as Philip Glass, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Ornette Coleman.

But choosing the Buchla as her other half came with its own unique set of complications. To watch her live performances is to see a graceful “choreography of movements” and yet the synth itself was bulky, would continually break and took years to get fixed, if it could be fixed at all. Travelling anywhere was particularly hazardous. “Something can break on the airline, the luggage handle smashes your machine. You never know if you’re going to have what you need to do the performance,” says Ciani.

Not only was there all this unpredictability, but Ciani also had a hard time getting people to understand what she was doing in the first place. Electronic music was so alien that it posed “a whole new world and language”. Her live television performance, to an incredulous-looking David Letterman, in 1980, underlines how, even then, after Kraftwerk, her talents were seen as bizarre. “Nobody even understood that the sound was coming out of the machine, it just didn’t compute,” she says. “It was so unknown that the connection couldn’t be made. It’s like when they say when Columbus came across the ocean, that the Indians didn’t even see the ship because they had no concept for ships.”

Even the forward-thinking minimal classical milieu of the day didn’t get it at first. Ciani sees a link between the emotionally affecting simplicity of her music and theirs but at the time it doesn’t sound as if that understanding worked vice versa. In 1974 she met Philip Glass and put her Buchla in his studio for a period. “We did electronic lessons for about a month or so, and in the end it just wasn’t for him.” Other composers were not as receptive. “Steve Reich said, ‘You should send all these machines to the moon and make them stay there!’” she laughs. “It’s so funny because Steve, in those days, openly hated electronic music instruments. And a couple of years ago I was at a big industry convention and a young fellow comes up to me. He’s an electronic musician, and he says, ‘I think you know my dad?’” And I just laughed out loud. I said, ‘It’s poetic justice, that Steve’s son is an electronic musician’.”

As a recording artist, the Buchla also had its limitations. “I went to all the record companies and I said, you know, give me a deal,” Ciani remembers, “and they said, ‘What do you do?’, and I said, ‘I play the Buchla’, and they say, ‘What’s that?’, and I said, ‘I’ll show you’.” But even a studio setup back then couldn’t accommodate her Buchla – or at least music execs couldn’t get their head around the fact that she didn’t need a band. They said, “Why don’t you sing?’, ‘Where’s the guitar?’, ‘You’re a girl’, you know, ‘You must sing’,” she continues. “There was no opening for it, and that’s how I got into commercials.”

The advertising world, she says, was “looking for something new; you want to be on the edge, you want to be different. The fact that they didn’t understand it already intrigued them”. So she started her own company, Ciani/Musica, which was almost completely unheard of for a female musician in those days. Essentially they did sound design, and much of it has been archived on the compilation Lixiviation on the British independent label Finders Keepers, who’ve been largely responsible for rereleasing Ciani’s work and bringing it to a wider audience in recent years. Notably, she added the electronic “swoosh” sound to Starland Vocal Band’s Afternoon Delight and FX for a 1977 disco version of the Star Wars soundtrack, among the odd B-movie horror and kung-fu films.

The noises she created for perhaps her most infamous sound effect, she says, were invented in a matter of minutes. “My brain was working at lightning speed in those days,” she laughs, of how she came up with Coca Cola’s signature pop, bubble and fizz. “I had been trying to get an appointment with the music director Billy Davis for over a year. He stood me up for the umpteenth time, so I marched over to his studio from his office and they said, ‘You can’t disturb him’, and I said, ‘He had an appointment with me’. I opened the door and I went in. It was brazen. But I was desperate, I was starving. I was in New York living on Canal Street for $75 a month, and I was propelled by hunger, really.”

“It just so happened that they were working on a Coca-Cola commercial. He said, ‘What do you do?’, and I said, ‘I play the Buchla. I make sounds’, and he said, ‘Well, can you do something in here?’. I don’t know what they had in mind, but I said, ‘Yes, I can’. He said, ‘What do you need?’. I said, ‘I need my Buchla’, and he said, ‘Well, go get it’. I went and got my Buchla and I came back’. I did it right there and then.”

Eventually her original, irreplaceable Buchla 200 model broke for good and, unhappy with its subsequent models, Ciani started making piano and acoustic music that would later come to be known as “new age”. She wasn’t bothered by the emerging strains of dance music rattling clubs at the time (“I loved to go to Studio 54 in the day, but to make that music, I thought, was a little boring”) and instead wanted to explore sounds that had “beauty and sensuality”. Her debut album, 1982’s Seven Waves, was inspired by the femininity of the waveform. “To be blunt about this, the male paradigm for sexuality is more that pumping rhythm,” she says, referring to electronic styles, “and the female paradigm for sensuality was a much slower span. And it was that slow, wave-like form.”

But it is the Buchla that has brought her back. Last year Finders Keepers Records rereleased Buchla Concerts 1975, a collection of Ciani’s original live recordings and she made the collaborative EP, Sunergy, with Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, her latter-day incarnation and fellow Buchla disciple. Ciani is also the subject of an upcoming documentary, A Live In Waves. Don was the one who encouraged Ciani to try her beloved instrument once more. The two had had a fractured relationship – she says he used to be a “tough cookie” and says sweetly, “we even had a little lawsuit at one point”, of when Don replaced her faulty Buchla with a synth she was less pleased with, and then wouldn’t let her return it. But when her recovery from breast cancer in her early 40s brought her back to California, the two reconnected – over a shared love of tennis. “He said, ‘If you want to get a new system, get it now because something’s going to happen’,” says Ciani wistfully. She settled on the 200e, a “21st-century rebirth of the 70s classic”. “I didn’t know he was going to sell his company.”

When we first speak, Ciani is in good spirits, preparing to go to Burning Man and packing her light-up clothing and “butterfly wings”. But Don Buchla died soon after, on 14 September 2016, and just a month after a long and ugly lawsuit against the company who bought his Buchla brand in 2012 was dismissed. When we talk again, Ciani is still grieving, but his death has given her shows greater purpose. “I’m still in that moment,” she says of her life without Don. “It’s become about performing on the Buchla 200-E, I want to communicate the potential for live performance that Don envisioned. My dedication now is to show that you can make music with these live: no samples, no pre-recorded [music], you just go out there and play this non-keyboard instrument.”

Besides, she adds, “I had a deal with him up in the sky and I said, look, as long as this machine works, I’m going to keep playing it, and when it breaks, I’ll stop.”

If others had as much of a storied career as Ciani, they probably wouldn’t bother looking forward to the future, but the resurgent interest in her music and the technology it uses is also what gives her hope. “It’s interesting to me to see the cycle of things recurring, that the young people are very much in a technological wonderment that we had in the 60s,” she says. “In the 60s, that new world was aborted to some degree. The idea of a synthesiser was taken over by cultural forces that didn’t understand the potential: ‘Oh, you can synthesise the sound of a flute’, ‘Can make the sound of a violin?’, [there was] this preoccupation with copying existing timbres. I thought it was a dead idea, that we missed the first time around and that who knew when or if it would be revisited?”

Today, though, she sees the potential for machine music in line with the futuristic frontiers that herself and Don Buchla once envisioned. “In my day I thought we would be where we are now, 30 years ago,” she says. “I thought electronic music would be everyplace, built into furniture! I designed a sofa where eight people could sit in a circle and everybody could adjust their pitch.”

It sounds like something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey but for Ciani, every day was living inside that hi-tech headspace. “I thought it would be built into homes, because for me it was built in,” she says of electronic music. “My Buchla was on all the time, and I would walk in [my house] and the sound would greet me, and it would make me feel a certain way, and I thought everybody’s going to have this. It didn’t happen, and maybe now it is happening.” She considers how she is playing Moogfest when she is Team Buchla, the rivalry between east and west coast long dissolved and overtaken by a desire to find a new musical realm together. If it sounds hippyish, perhaps that’s because it always has been.

“It’s a conceptual field now,” says Ciani. “Rhythm to a higher level of consciousness.”

- Suzanne Ciani plays Moogfest, 18-21 May; Sonar, Barcelona, 15-17 June; Terraforma, Milan, 23-25 June

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion